-

Man City smash Palace to fire title warning, Villa extend streak

Man City smash Palace to fire title warning, Villa extend streak

-

Arshdeep helps India beat South Africa to take T20 series lead

-

Zelensky meets US envoys in Berlin for talks on ending Ukraine war

Zelensky meets US envoys in Berlin for talks on ending Ukraine war

-

'Outstanding' Haaland stars in win over Palace to fire Man City title charge

-

Man City smash Palace to fire title warning, Villa extend winning run

Man City smash Palace to fire title warning, Villa extend winning run

-

Napoli stumble at Udinese to leave AC Milan top in Serie A

-

No contact with Iran Nobel winner since arrest: supporters

No contact with Iran Nobel winner since arrest: supporters

-

Haaland stars in win over Palace to fire Man City title charge

-

French PM urged to intervene over cow slaughter protests

French PM urged to intervene over cow slaughter protests

-

'Golden moment' as Messi meets Tendulkar, Chhetri on India tour

-

World leaders express horror, revulsion at Bondi beach shooting

World leaders express horror, revulsion at Bondi beach shooting

-

Far right eyes comeback as Chile presidential vote begins

-

Marcus Smith shines as Quins thrash Bayonne

Marcus Smith shines as Quins thrash Bayonne

-

Devastation at Sydney's Bondi beach after deadly shooting

-

AC Milan held by Sassuolo in Serie A

AC Milan held by Sassuolo in Serie A

-

Person of interest in custody after deadly shooting at US university

-

Van Dijk wants 'leader' Salah to stay at Liverpool

Van Dijk wants 'leader' Salah to stay at Liverpool

-

Zelensky in Berlin for high-stakes talks with US envoys, Europeans

-

Norway's Haugan powers to Val d'Isere slalom win

Norway's Haugan powers to Val d'Isere slalom win

-

Hong Kong's oldest pro-democracy party announces dissolution

-

Gunmen kill 11 at Jewish festival on Australia's Bondi Beach

Gunmen kill 11 at Jewish festival on Australia's Bondi Beach

-

Zelensky says will seek US support to freeze front line at Berlin talks

-

Man who ploughed car into Liverpool football parade to be sentenced

Man who ploughed car into Liverpool football parade to be sentenced

-

Wonder bunker shot gives Schaper first European Tour victory

-

Chile far right eyes comeback as presidential vote opens

Chile far right eyes comeback as presidential vote opens

-

Gunmen kill 11 during Jewish event at Sydney's Bondi Beach

-

Robinson wins super-G, Vonn 4th as returning Shiffrin fails to finish

Robinson wins super-G, Vonn 4th as returning Shiffrin fails to finish

-

France's Bardella slams 'hypocrisy' over return of brothels

-

Ka Ying Rising hits sweet 16 as Romantic Warrior makes Hong Kong history

Ka Ying Rising hits sweet 16 as Romantic Warrior makes Hong Kong history

-

Shooting at Australia's Bondi Beach kills nine

-

Meillard leads after first run in Val d'Isere slalom

Meillard leads after first run in Val d'Isere slalom

-

Thailand confirms first civilian killed in week of Cambodia fighting

-

England's Ashes hopes hang by a thread as 'Bazball' backfires

England's Ashes hopes hang by a thread as 'Bazball' backfires

-

Police hunt gunman who killed two at US university

-

Wemby shines on comeback as Spurs stun Thunder, Knicks down Magic

Wemby shines on comeback as Spurs stun Thunder, Knicks down Magic

-

McCullum admits England have been 'nowhere near' their best

-

Wembanyama stars as Spurs stun Thunder to reach NBA Cup final

Wembanyama stars as Spurs stun Thunder to reach NBA Cup final

-

Cambodia-Thailand border clashes enter second week

-

Gunman kills two, wounds nine at US university

Gunman kills two, wounds nine at US university

-

Green says no complacency as Australia aim to seal Ashes in Adelaide

-

Islamabad puts drivers on notice as smog crisis worsens

Islamabad puts drivers on notice as smog crisis worsens

-

Higa becomes first Japanese golfer to win Asian Tour order of merit

-

Tokyo-bound United plane returns to Washington after engine fails

Tokyo-bound United plane returns to Washington after engine fails

-

Deja vu? Trump accused of economic denial and physical decline

-

Vietnam's 'Sorrow of War' sells out after viral controversy

Vietnam's 'Sorrow of War' sells out after viral controversy

-

China's smaller manufacturers look to catch the automation wave

-

For children of deported parents, lonely journeys to a new home

For children of deported parents, lonely journeys to a new home

-

Hungary winemakers fear disease may 'wipe out' industry

-

Chile picks new president with far right candidate the front-runner

Chile picks new president with far right candidate the front-runner

-

German defence giants battle over military spending ramp-up

Grey area: chilling past of world's biggest brain collection

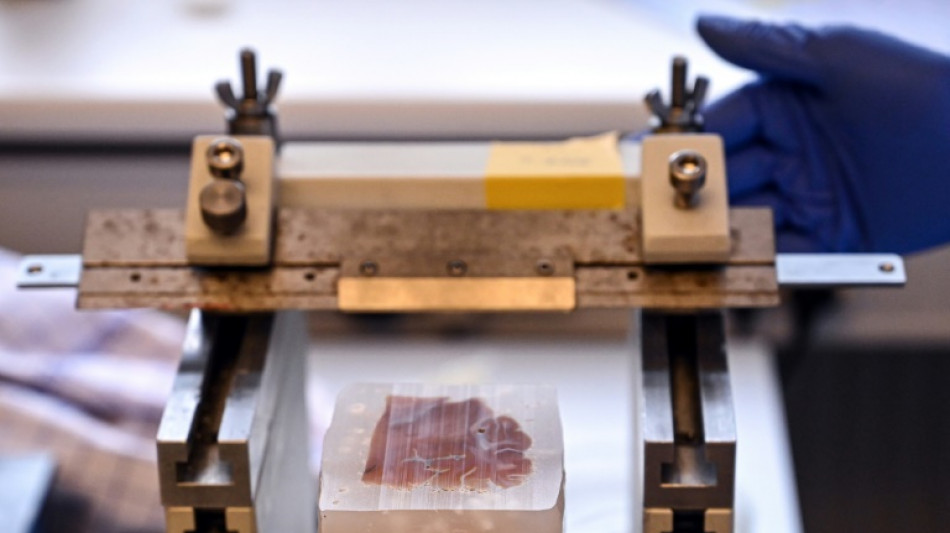

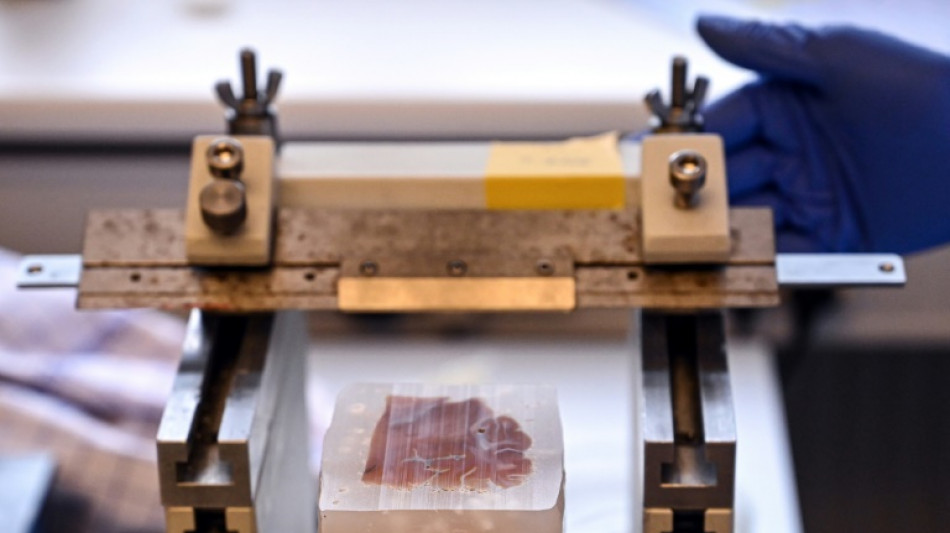

Countless shelves line the walls of a basement at Denmark's University of Odense, holding what is thought to be the world's largest collection of brains.

There are 9,479 of the organs, all removed from the corpses of mental health patients over the course of four decades until the 1980s.

Preserved in formalin in large white buckets labelled with numbers, the collection was the life's work of prominent Danish psychiatrist Erik Stromgren.

Begun in 1945, it was a "kind of experimental research," Jesper Vaczy Kragh, an expert in the history of psychiatry, explained to AFP.

Stromgren and his colleagues believed "maybe they could find out something about where mental illnesses were localised, or they thought they might find the answers in those brains".

The brains were collected after autopsies had been conducted on the bodies of people committed to psychiatric institutes across Denmark.

Neither the deceased nor their families were ever asked permission.

"These were state mental hospitals and there were no people from the outside who were asking questions about what went on in these state institutions," he said.

At the time, patients' rights were not a primary concern.

On the contrary, society believed it needed to be protected from these people, the researcher from the University of Copenhagen said.

Between 1929 and 1967, the law required people committed to mental institutions to be sterilised.

Up until 1989, they had to get a special exemption in order to be allowed to marry.

Denmark considered "mentally ill" people, as they were called at the time, "a burden to society (and believed that) if we let them have children, if we let them loose... they will cause all kinds of trouble," Vaczy Kragh said.

Back then, every Dane who died was autopsied, said pathologist Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen, the director of the collection.

"It was just part of the culture back then, an autopsy was just another hospital procedure," Nielsen said.

The evolution of post-mortem procedures and growing awareness of patients' rights heralded the end of new additions to the collection in 1982.

A long and heated debate then ensued on what to do with it.

Denmark's state ethics council ultimately ruled it should be preserved and used for scientific research.

- Unlocking hidden secrets -

The collection, long housed in Aarhus in western Denmark, was moved to Odense in 2018.

Research on the collection has over the years covered a wide range of illnesses, including dementia, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression.

"The debate has basically settled down, and (now people) say 'okay, this is very impressive and useful scientific research if you want to know more about mental disease'," the collection's director said.

Some of the brains belonged to people who suffered from both mental health issues and brain illnesses.

"Because many of these patients were admitted for maybe half their life, or even their entire life, they would also have had other brain diseases, such as a stroke, epilepsy or brain tumours," he added.

Four research projects are currently using the collection.

"If it's not used, it does no good," says the former head of the country's mental health association, Knud Kristensen.

"Now we have it, we should actually use it," he said, complaining about a lack of resources to fund research.

Neurobiologist Susana Aznar, a Parkinson's expert working at a Copenhagen research hospital, is using the collection as part of her team's research project.

She said the brains were unique in that they enable scientists to see the effects of modern treatments.

"They were not treated with the treatments that we have now," she said.

The brains of patients nowadays may have been altered by the treatments they have received.

When Aznar's team compares these with the brains from the collection, "we can see whether these changes could be associated with the treatments," she said.

Y.Aukaiv--AMWN